Do you have Pennsylvania German history in your family? Or German, Swiss, or French ancestors that immigrated to the east coast in the 18th and 19th century? You may be surprised to learn about early American frakturs (pronounced “frok-tours”), a type of folk art often overlooked by genealogists, that may contain important information about these people’s lives.

From The National Archives: Revolutionary War Frakturs collection on flickr, for Philip Frey of Pennsylvania, ca 1800 - ca 1900. Frakturs in this collection were generally used for bounty-land warrant applications or Revolutionary War pensions, to prove lineage. No known copyright restrictions.

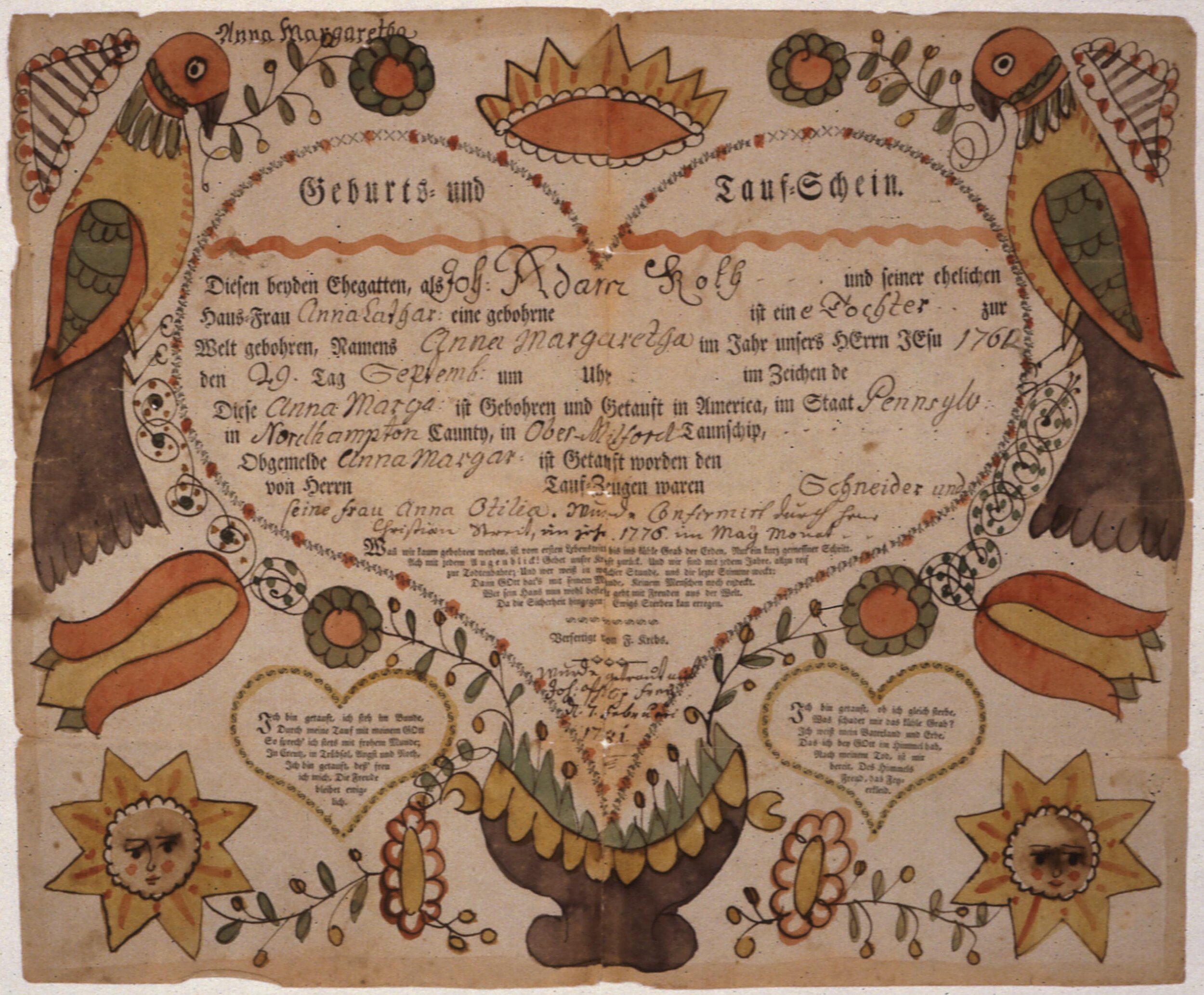

Frakturs were illustrated manuscripts, created from mainly 1740 to 1860, with some as late as 1900. They were made with ink and watercolor, first by hand and later printed and hand-decorated or colored. They were often filled with motifs of angels, tulips and other flowers, hearts, stars, and birds (all of which are open to symbolic interpretation and linked to later prevalence within Dutch hex signs), as well as mythical creatures like mermaids and unicorns, and even a few historical figures like George Washington.

The name “fraktur” comes from the latin fraktura, meaning a “breaking apart”, referring to the broken or fractured style of writing and similar style to the German typeface of the same name. This style of art was once called Frakturschriften, or “Fraktur Writings” (Library of Congress, Conner, and Roberts). The text was either in German or English, with a main entry in the center and often poems or quotes on the sides.

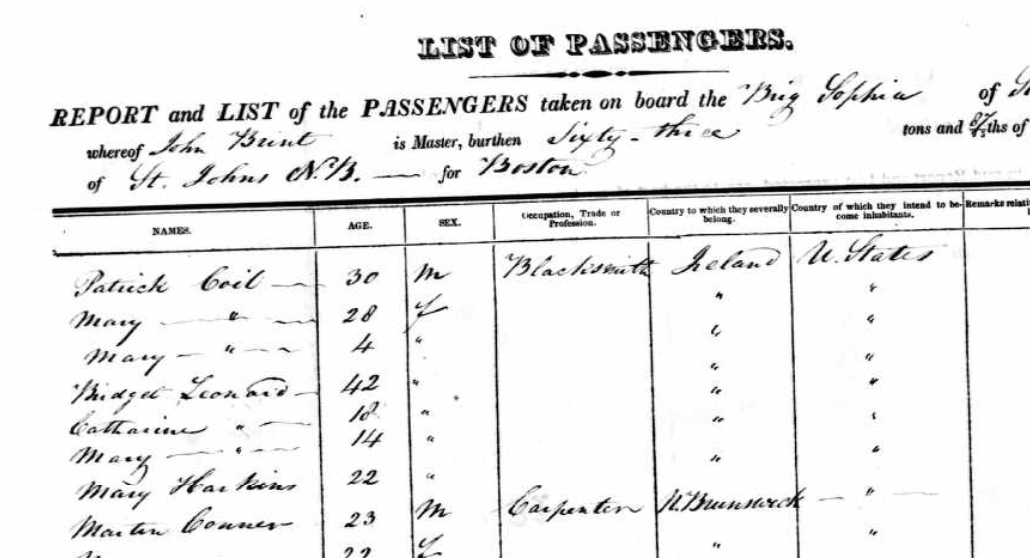

These frakturs were used to document important events and milestones in a person’s life, and can contain a wealth of genealogical information. For example, the Geburts and the Taufscheins, or the birth and baptism certificates, were often the only record of birth for an individual as they predated vital record keeping by local government. They contained names, family members, witnesses, locations, dates, and the name and domination of the clergyman. Other types of frakturs include the Haus Segen, or house blessing, the vorschrift, or writing examples, and bucherzeichen, or bookplates.

”Certificate of birth : David Kraatz was born on the 12th day of August A.D. 1824 in Alsas Township, Berks County, Pa., 1824”. An example of a cut-paper Fraktur, from the collection Pennsylvania German broadsides and Fraktur, 1750-1979. Penn State University Libraries Digital Collection, Public Domain.

It should be noted that “the taufschein and the vorschrift form the vast bulk of fraktur documentation. Wedding and death certificates are relatively rare.” (Library of Congress, Conner, and Roberts). For those interested in researching your ancestors, definitely start with the birth and baptism certificates by browsing online collections, which we’ve linked for you further down this post.

Frakturs were brought to the southeast Pennsylvania area by German-speaking immigrants, hailing from the Rhineland area of Europe and nearby Switzerland. Most belonged to the Lutheran and Reformed churches, but also Anabaptist (Amish, Mennonite, etc.) and others. Frakturs have also been found in other places the Pennsylvania Dutch migrated, including Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, Ohio, North Carolina, New Jersey, and parts of Canada.

Fraktur of John Hoagland of New Jersey and family, from the National Archives: Revolutionary War Fracturs collection on flickr. Frakturs in this collection were generally used for bounty-land warrant applications or Revolutionary War pensions, to prove lineage. No known copyright restrictions.

Though a form of frakturs existed in their homelands (or predecessors like the Patenbrief and the Goettelbrief), the type of art and tradition that developed in colonial America is unique to the new culture.

They were usually produced by ministers and school teachers, for those they came into contact with in their daily lives, or for their family and friends. The work was done as a side gig to their main profession. Later they would design and print blank forms to be hand colored with text entered by the families, though some communities had earlier access to printing presses than others.

An example of a birth certificate and baptismal fraktur. Caption reads: “Geburts- und Tauf- schein for Susanna Walder, 1825 Sept. 20-1825 Nov. 6” from Penn State University Libraries Digital Collection. More genealogy information in the description on their website. Public domain.

While the vorschrift, or writing samples, would be proudly displayed in schools and at home, the other types of more decorative fraktur were not made for hanging on the walls for all to see. In a religious culture where “public art, art for display, was forbidden”, these documents were personal and private treasures. They stored them hidden away “in Bibles or other large books, pasted onto the inside lids of blanket chests, or rolled up in bureau drawers” (Library of Congress et al). It was not uncommon for taufschein to be buried with an individual.

Today most belong to museums and university collections, prized by collectors and sold at auctions for thousands of dollars. Handmade frakturs seem to be worth more than printed versions, as do aesthetically pleasing and unique designs, and those in good condition. Be wary of fakes and aware of modern reproductions, and always get any finds properly appraised.

Luckily for those of us interested in the information these works of art contain, many of these collections can be browsed online and used for research remotely.

Notice the similarities between the earlier birth certificate of Susanna Walder above, from 1825, and this one from 1844. Same motiffs of angels and birds, though this one includes a seal of the United States in the top middle, perhaps indicative of newfound patriotism. From Penn State University Libraries Digital Collection, title reads: “Geburts- und Tauf-Schein for Emeleine Sara Anna Hix, 1844 Nov. 2-1844 Dec. 25”. Public domain.

Online Browsable Collections of Historical Frakturs:

F&M Pennsylvania German Fraktur Collection, from the Franklin & Marshall College Library

MESDA: Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts; Fraktur Collection

Penn State University Libraries Digital Collections: Pennsylvania German Broadsides and Fraktur

Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center at Kutztown University

Source List & Additional Online Reading:

Beach, Laura. “Drawn with Spirit: Pennsylvania German Fraktur from the Joan and Victor Johnson Collection”. Accessed online February 2021, from: https://www.antiquesandthearts.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/German.pdf

“Fraktur” from Treasures on Trial: The Art and Science of Detecting Fakes. http://treasuresontrial.winterthur.org/evidence/fraktur/

Franklin & Marshall College Library, “Fraktur”. Accessed online at: https://library.fandm.edu/archives/gaimprints/fraktur

Krahn, Cornelius, Harold S. Bender, Ethel Ewert Abrahams, Mary Jane Lederach Hershey and Carolyn C. Wenger. “Fraktur (Illuminated Drawing)”, Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Accessed online February 2021, from: https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Fraktur_%28Illuminated_Drawing%29

Library of Congress, Jill Roberts, Paul Connor, and American Folklife Center. Pennsylvania German Fraktur And Printed Broadsides: a Guide to the Collections In the Library of Congress. Washington: Library of Congress, 1988. Found online at Hathi Digital Trust: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/006934791

Moyer, Forrest. “How we identify a fraktur artist,” April 15, 2020. Mennonite Heritage Center. https://mhep.org/how-we-identify-a-fraktur-artist/

Shelley, Donald A. The Pennsylvania German style of illumination. New York: New York University, 1953. Found online at Hathi Digital Trust: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000378944

Wikipedia, “Fraktur (folk art)” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fraktur_(folk_art)

Wikipedia, “Pennsylvania Dutch” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pennsylvania_Dutch

“Diese Sing-Noten-Buchlein gehoret Catarina Weillerin, 1788” from Penn State University Libraries Digital Collections. A beautiful example of a manuscript songbook fraktur, belonging to a Catarina Weillerin of Chester County, Pennsylvania, from 1788. Public domain.

Offline Suggested Reading:

Earnest, Corrine P., Rusell D. Earnest. The Heart of the Taufschein: fraktur and pivotal role of Berks County, Pennsylvania, Kutztown, PA, Pennsylvania German Society, 2012.

Shelley, Donald A. The Fraktur-Writings or Illuminated Manuscripts of the Pennsylvania Germans, Pennsylvania German Folklore Society, 1961.

Stopp, Klaus. The Printed Birth and Baptismal Certificates of the German Americans. Mainz, Germany; East Berlin, PA: K. Stopp, 1997.